In Weymouth, they called him Joe Horse.

His real name was Joseph Cavallo, but nobody called him that. Not at Denly’s, not on Lake Street, not at the Water Department where he worked. You see, Cavallo means horse in Italian, and Joe wore that name like a crown. He was a local legend. The kind of guy who walked into the bar and turned it into a party, even if no one else was there.

When he walked into Denly’s, everyone would shout his name like Norm from Cheers:

“Joe Horse!”

He’d raise his glass to the bar in that thick Weymouth drawl shaped by his Old World roots and belt out for all the patrons to hear:

“Cent’anni!”

Cent’anni is an Italian saying that means “May you live 100 years.”

Joe was born on December 23, 1907, just before Christmas. He crossed the Atlantic from Foggia, Italy to America with my grandfather, Mike Cavallo—or Pa, as I called him—on a steamship in February 1912, just after turning five. That crossing, rough and cold, marked the beginning of a life spent in the margins between hard work and good times.

When he was thirteen, Joe was helping his dad make whiskey in backyard stills, Prohibition-style. One day, he tried to uncap a bottle too fast, and the pressure caused the cap to fly up and blow out his eye. For the rest of his life, Joe had just one eye, but he never seemed to mind. If anything, it made him cooler to the kids. It was a badge of mischief. A mark of old-school toughness.

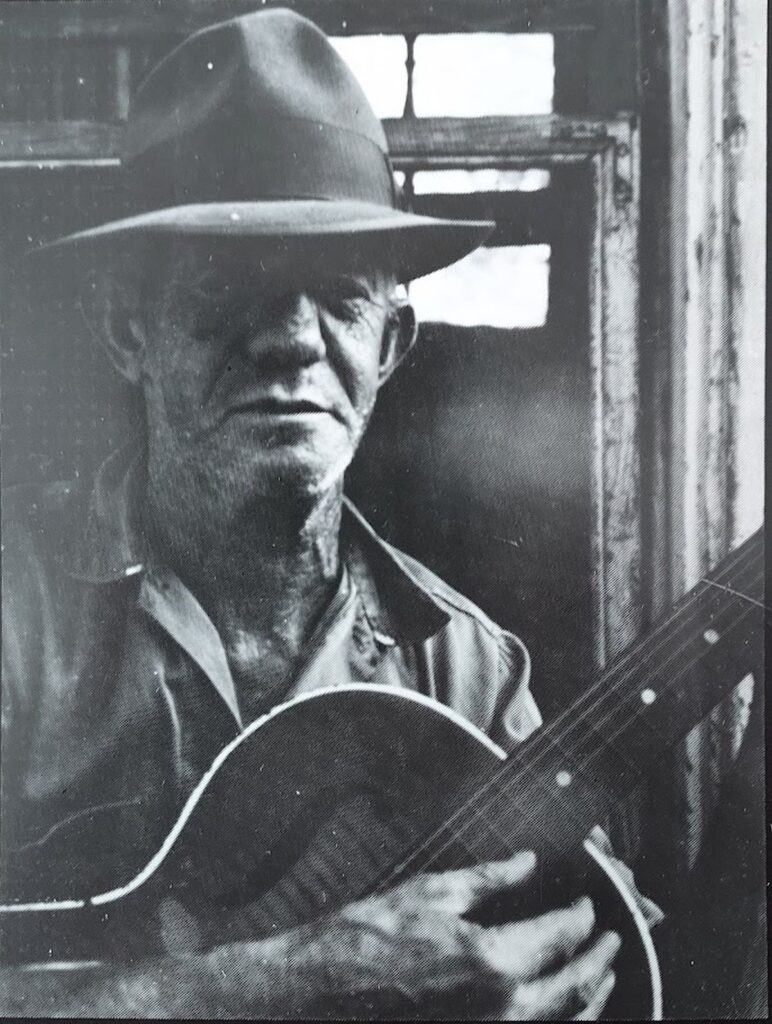

Joe never married. He never had kids. But he lit up the house like a favorite uncle should. He played the piano and the guitar. He sang old Italian songs after the bar had closed and the rest of the world was trying to sleep. Even when his hands smelled like rust and his breath like whiskey, he was always a gentleman. Always smiling. Always giving.

On paydays, after handing over rent money to his mother, he’d walk down Lake Street with a bag of Hoodsie ice cream cups for Angie, Loretta, Peter, and any of the neighborhood kids hanging around the block. Balzac, Grandma’s dog, got a Fudgsicle—every time.

And Joe never went anywhere without his Camel cigarettes.

He worked for the Weymouth Water Department, did his job, punched out, and walked straight down to Denly’s for his drink. Most nights, he’d stumble back up Lake Street, crash onto the porch, and call it a night. He had a big tab at Denly’s. Mike was always afraid that he was going to get stuck with it.

One night, when my dad was a boy, he went to check on Uncle Joe, thinking he was asleep under a blanket on the porch couch. When he pulled the blanket back, he gasped—it wasn’t Joe. It was half a pig, waiting for Grandma to carve it up. Just another night on Lake Street.

Some nights, though, Joe didn’t even make it to the porch. When the walk was too long or the buzz too strong, the family would wake up and find him asleep in the bushes, half-covered in hydrangeas and grapevines, like some kind of Roman ruin.

That was just part of who he was.

By 1971, Joe was 63 and had a plan: work two more years for the town, then retire and join his brothers Frank and Tony in Arizona, where they were already enjoying their golden years under the desert sun.

But life had other plans.

Joe wasn’t feeling great that Saturday, June 19, 1971. He had a deep cough he couldn’t shake, one that even made him say, Maybe I oughta see a doctor. But he didn’t go. Joe never went to the doctor.

That morning, a buddy stopped by needing help painting a house. He promised Joe a stop at Denly’s afterward. That was enough motivation for Joe to put on his boots and go.

That night, Joe walked into Denly’s, same as always. He took his usual spot at the end of the bar. The crowd greeted him with the usual:

“Joe Horse!”

Tex Remonidi, the Denly’s bartender, gave him a nod. Tex had a heavy Italian accent and, confusingly, the nickname of a cowboy. No one knows how he got the name Tex, especially not in a town full of Italians, but if you wanted a glass of red and a story, Tex was your guy.

“Your usual?” he asked.

Joe didn’t answer. He didn’t have to. Tex turned around, reached for the bottle, and poured a shot of whiskey. But when he turned back…

Joe was gone.

That struck Tex as odd. He placed the drink on the bar where Joe had been, thinking maybe he’d just stepped away.

But Phyllis, the waitress, spotted him from the dining room.

“Tex! Call an ambulance! Joe’s on the floor!” she screamed.

Minutes later, Weymouth Police and Fire had him in the back of an ambulance and on the way to South Shore Hospital.

Phyllis called the house on Lake Street looking for Mike or Susie (my grandmother), but Angie picked up. She rushed to the hospital and found a nurse flipping through the phone book.

“What’s the last name?” the nurse asked.

“Cavallo,” Angie said.

The nurse paused, still on the “C” section, but Angie had already seen a familiar pair of work pants and boots under a curtain in the next room.

“I think that’s my uncle in there.”

The nurse set the phone book aside, pulled out a wallet, and then showed her a driver’s license. “Can you confirm this is your uncle?”

Angie nodded. “Yes. That’s my Uncle Joe.”

“I was trying to find your number,” the nurse said gently. “I’m so sorry, honey. Your uncle has passed.”

Angie collapsed in disbelief. She had just seen him that morning, getting ready to help his friend paint.

Back on Lake Street, she had to break the news to her parents. Mike didn’t believe it.

“He probably got hit by a car stumbling home,” he said. “He’s always tripping up that hill.”

Angie shook her head. “Dad, he isn’t hurt. He isn’t coming home. Something happened at Denly’s.”

Still in disbelief, Nana called the hospital to verify. Angie was furious.

“Ma, why are you calling? I told you everything I knew.”

Mike, unable to sit still, walked down to Denly’s. Tex met him with misty eyes and an outstretched hand.

“Mike… I’m sorry for your loss,” he said. “Joe’s tab—it’s on the house. May he rest in peace.”

A few days later, at Joe’s wake, the family did something no one questioned. They slipped a nip of whiskey and a pack of Camels into the inside pocket of Joe’s suit jacket. A final toast. A final smoke.

No one really knows if Joe ever touched that last glass. Tex told Pa he hadn’t had a sip. Maybe that’s true.

But in my mind, I like to believe he saw it, his whiskey, right there on the bar. Maybe he felt the love in that room. Maybe he heard the chorus of “Joe Horse!” echoing in his ears one last time. And just before the lights went out, he raised his glass towards heaven, and he whispered it to himself:

“Cent’anni.”

And may you live 100 years, too.

Oh Matt, I never heard this whole story, just bits of it! I’m glad you’re recording all Angie’s memories. Keep it going!

❤️ mom